“What if we simply…”: A history of AI in two-line paper summaries (Part One)

Before the deep learning revolution

Short form is good actually

Paper abstracts are too long for me.

When I’m learning about a new field, as I have been with LLMs recently, I need something so short I can instantly remember it when I recall the paper.

So over the last few months every time I’ve read an important paper, I have written a two line summary of them. A kind of abstract’s abstract.

Line one: a question beginning with “What if we simply…”.

Line two: the answer.

Which matches my experience that the best research outcomes have arisen from someone asking “what if we simply do X differently?”.

I started doing this for modern LLM papers, then realized I could extend the same format backwards through the history of ML and it might be useful to some people.

I split this into three parts.

1. pre-deep-learning machine learning (before 2012)

Most of this I learned at grad school.

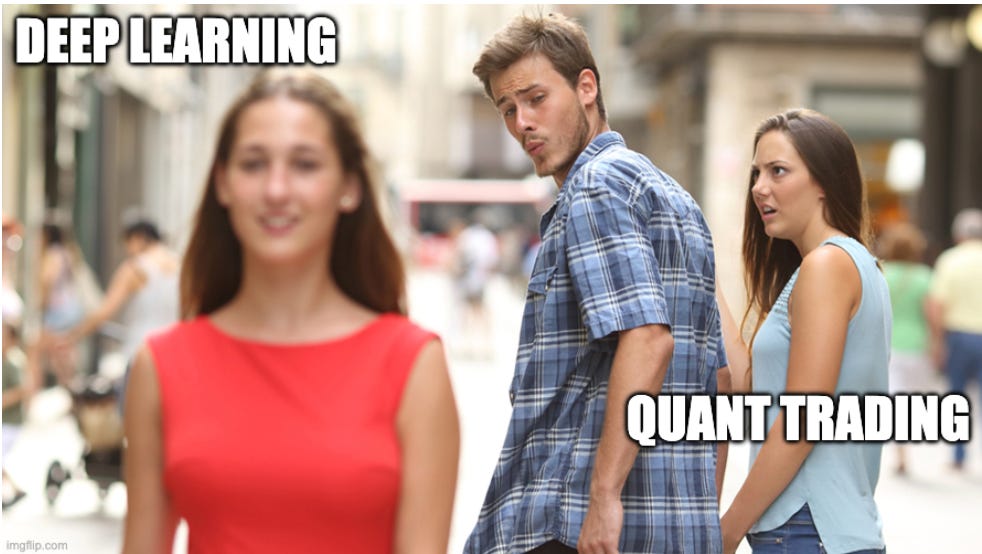

I graduated in 2015, the same year that Andrej Karpathy gave his deep learning course (CS231N) for the first time. I audited it thinking “huh wow this is a great course and he’s a great teacher”. A couple weeks later my team beat his in a grad student trivia contest, so I decided I was smarter than Andrej, I stopped doing his coursework, and took a job in quant finance (since that’s where all the smart kids went at the time).

Anecdotally that single course pushed the graduate students in the year below me away from quant finance and towards computer vision and deep learning. It turned out that Andrej was a great teacher and deep learning was kind of important after all.

2. pre-LLM deep learning (2012 - 2020)

Most of this I learned while I was working as a quant.

Increasingly, I was looking over at this new field of Deep Learning (mostly applied to computer vision), then looking back at the ML we were doing in production which was both highly profitable and embarrassingly simple in comparison.

Nonetheless I remained happy with my decision. Quant finance was interesting, difficult, sometimes well-paid, fast-paced, and I had made a bunch of friends at the company.

3. LLMs (2020 - now)

Most of this I’ve learned in the past six months.

When GPT2 (2019) came out I had my first thought of “oh they got a machine to write paragraphs? I might be in the wrong field now”. I began getting back up to speed in this new genre of model while our models continued to be basic at least in comparison. But then COVID arrived and volatility spiked. HFTs around the world rejoiced.

I remained in finance for another four years and left in 2024.

Final caveats

I’ve read most of the later papers in this series. I haven’t read most of the earlier papers since I learned about them from textbooks and they’re behind paywalls in many cases. Pretty much no-one should be reading original papers from before 2010 unless it’s for historical reasons. But I still like the idea and thought it should be extended to its logical conclusion.

Part One - machine learning before deep learning

Before we had deep learning we had no funding machine learning and statistics.

Foundations of linear models

Least Squares (1805) | Paper

What if we simply found the line that minimizes the sum of the squared errors when we fit x to y?

Answer: Oh hey it’s neat that we can get a direct formula for it from the data. This became known as linear regression.

Regression to the Mean (1886) | Paper

What if we simply measured the height of parents and their children?

Answer: Tall parents have shorter kids, short parents have taller kids.

Amusing note: Galton originally called this “regression to mediocrity” which is a fantastic insult that I will now be using should any rambunctious scallywag inconvenience me.

Logistic Regression (1958) | Paper

What if we simply squashed the output of linear regression to be between 0 and 1?

Answer: Now we can do classification. Also this is secretly what a neural net with no hidden layers is doing.

Neural Nets rise and then fall

The Perceptron (1958) | Paper

What if we simply used inspiration from biology and used a weighted sum of inputs to decide if a neuron fires?

Answer: It learns! As long as your problem can be solved with a straight line, which most cannot.

Perceptrons have a problem (the XOR Problem) (1969) | Wiki

What if we simply proved that a single layer neural net cannot solve the XOR problem (e.g., inputs are different → True)?

Answer: Funding for neural nets evaporates overnight, causing the first “AI Winter.”

For more detail on the origins of the perceptron and its downfall, I liked this substack piece on it.

Backpropagation (1986) | Paper

What if we simply used the chain rule to figure out which weights caused the error and update them appropriately?

Answer: You can train multi-layer networks now! I’m sure this is the last time we have problems training deep networks.

Universal Approximation Theorem (1989) | Paper

What if we simply proved that a neural net with just one hidden layer can represent any mathematical function?

Answer: A single hidden layer net can represent anything. Training it to represent something useful is a different problem.

Post Office Zipcode Reading (1989) | Paper

What if we simply trained a multi layer neural net on handwritten digits?

Answer: This works! A neural network has finally got a job. AGI by 1992 baby!

You’d think after this big win, interest in neural nets would continue but for a lot of reasons:

lack of compute

lack of institutional interest

other methods like random forests and boosting were genuinely very good

other methods like SVM sounded fancier

interest actually died down.

By 2015 my Stat-302 course was teaching neural nets at the very end of the course as an afterthought, like “oh by the way there’s this other technique I suppose I should tell you about that you can use to do regression”. That course has, uh, since been removed from the syllabus.

Trees & Ensembles

Why rely on one smart model when you can rely on 1000 dumb ones?

CART (Decision Trees) (1984) | Book/Ref

What if we simply split the data into groups by asking a series of Yes/No questions and call it a tree?

Answer: We get a flowchart that can predict outcomes (and unlike a neural net, humans can actually read it).

AdaBoost (1995) | Paper

What if we simply trained a new model to focus more on the examples the last model got wrong?

Answer: We get a group of weak models (that are only slightly better than guessing) but they can combine to form a strong model. Cool that this works. Maybe we should do more of this.

Random Forests (2001) | Paper

What if we simply trained 100 trees on random subsets of the data and averaged their predictions?

Answer: Turns out just averaging a bunch of weak but slightly different models gives you quite a strong model.

Gradient Boosting (2001) | Paper

What if we simply trained each new tree to predict the errors of the previous tree?

Answer: Each tree cleans up after the last one. Turns out this is one of the best ideas in ML.

Boosted trees were the thing used in production models across the tech industry for serving ads for many many years. They dominated Kaggle competitions as well. So although the next paper came out after 2013, I’m including it here since it’s such an important piece of the pre-DL setup. They were slow to train but very good once trained.

XGBoost (2016) | Paper

What if we simply engineered the hell out of gradient boosting to run on hardware efficiently?

Answer: Now anyone can do fast boosting, this method wins every Kaggle competition for years.

Regularization & The Kernel Era

Sometimes the models get too big and can memorize the dataset entirely. This is bad. Let’s stop doing this.

Ridge Regression (1970) | Paper

What if we simply penalized the weights, w, in our linear regression by their squared value, rather than just minimizing the error on the data?

Answer: The model no longer gets tripped up by highly correlated variables.

Support Vector Machines (SVM) (1995) | Paper

What if we simply drew the decision line down the middle of the widest possible street between the classes?

Answer: We get a new model type that lets us do cool fun theory on it and sends academia down this path.

The Kernel Trick (1992) | Paper

What if we simply projected the data into infinite dimensions without actually calculating the coordinates?

Answer: Wait what, we can “project data into infinite dimensions without infinite compute”? Yes. Yes we can. Can you see why academics loved this and didn’t love the neural net work that had no neat theory behind it?

Lasso (1996) | Paper

What if we simply penalized the absolute size of the weights in our model instead of the squared weights like in ridge?

Answer: That ridge regression model sure had some nice properties. Would be a shame if something came along that was on average worse but was more interpretable and got more citations than anything else in stats history.

By 2012 we had a set of modeling tools that I had learned about at grad school and by 2015 I was ready to wield them in industry.

But then the AlexNet paper came along, beat the state of the art in computer vision, and changed the direction of the field.

More on that in the next post.

Brilliant synthesis of pre-deep learning ML history. The kernel trick explanation really captures why academics gravitated toward SVMs over neural nets, becuase there was actual theory to publish. Its fascinating how XGBoost managed to dominate Kaggle for years even after AlexNet, which shows how much inertia there was inthe industry despite the obvious potential of deep learning.

This does a great job of getting to the heart of ML research motivations which is often obfuscated either by overly complex papers or basic blog posts. Look forward to the next post!