Where have the International Math Olympiad Gold Medallists Ended Up? Part One of Three

North Korean defectors, Buddhist monks, and Twitter-famous quants

Table of contents

Motivations

What do a North Korean defector, the first female Fields medallist, and a Buddhist monk-turned-therapist-influencer have in common? They all participated in the most prestigious high school math competition in the world: the International Mathematics Olympiad (IMO).

The 65th IMO has just come to a close (team USA won 🇺🇸) and I wanted to dig deep into the outcomes of the most successful participants from this competition.

Why do I care so much?

I was an enthusiastic but mediocre participant in the British Mathematical Olympiad (BMO) from 2008-2010. The best performers on the BMO go on to represent the UK at the IMO. Rather than describe how badly I did, I have just annotated the distribution of marks from an equivalent year. I was far from representing the UK. We must have had some geniuses on the team, I thought.

To my compounding horror I discovered that most of these students were, in turn, being outcompeted at the next level up! In 2010, the six person UK team got one gold, one silver, and two bronze medals between them and were ranked 25th. That same year every single member of the team from China won gold. Below is a histogram of the IMO marks.

Who were these genius kids that were operating at a level above the people who were operating at a level above me? Where did they go after such early mathematical success and prestige? Just as importantly, how could I preserve my ego and avoid them forever?

Multiple documentaries [1, 2] about them imply I was not alone in my curiosity about the outcomes of these precocious youths.

Are they all quants?

While I never represented the UK at ‘maths’, I was good enough to get a job at a quantitative finance firm. Just as the nightmares of inaccessible levels of intellect were fading I discovered that a multiple IMO gold medallist was in my starting cohort. So for the first time, I came across one in real life.

He is a wonderful guy and by all accounts he is a delight to work with. We trained together and by the end it was clear that he was quite a lot smarter than me. There’s a trope that IMO medallists all get lured into quant finance, leading to tweets like this one:

But, as any good quant knows, anecdote is no substitute for data.

This interaction had piqued my curiosity again. Who were these gold medallists? What were they doing now? Was I doomed to interact with them due to my chosen career path of quant finance?

In this three-part, six-sectioned post I’ll attempt to answer these questions and more.

Section One describes previous work others have done, in particular Professor Tolga Yuret, who, in my opinion, has written the definitive work on the subject for IMO participants up to 2005. He was also extremely prompt and helpful answering my questions.

Section Two describes the dataset along with the data-gathering process and biases in the data collection methods. It then looks at some initial analyses to sanity check my dataset.

Section Three begins the analysis and looks at where the gold medallists went for undergrad; which countries and which institutions.

Section Four looks at where they went post-graduation and answers the age-old question “Do all IMO gold medallists end up in quant finance?”.

Section Five looks at notable changes in any of these patterns over time.

Section Six looks at some specific cases: including the monk, the defector, and the Fields medallists. I also attempt to guess at some who ended up at the two most secretive hedge funds in the USA: Renaissance Technologies and TGS Management.

The rest of this post will be sections one and two. Part two of three is out here.

Section One: Have other people already looked into gold medallists outcomes?

I sorely hoped something had already been written on this so I wouldn’t have to write this post, but I couldn’t find exactly what I wanted. Some were close, though.

Blogs

A few blog posts have talked about where a small handful of IMO participants ended up:

Russell Lim, an Australian high school math teacher, went through the recent history of the IMO hall of famers.

Professor Andrew Gelman wrote about where his 1980 training class are now.

MIT have celebrated them in the past.

Vinod Aravindakshan, an IIT professor, did it specifically for Indian gold medallists.

Peter Taylor, who ran the Australian team, did it for Australian IMO competitors.

Professor Joe Gallian did it for winners of the Putnam Exams which are the US university equivalents and have a heavy overlap with IMO winners.

Papers

There are a few papers that talk about IMO participant outcomes at scale.

Most notably is this paper written by Professor Tolga Yuret who gathered data on the 1986-2005 IMO medallists. Yuret did a very comprehensive job showing statistics about where these medallists ended up. He has more rows and columns of data than I do. He includes more candidates and more information about those candidates. This was nearly the report I wanted. But as someone that took the BMO in 2008, I was curious about more recent outcomes than 2005. I’ll use his results to compare to mine at various points in this post so I won’t summarize too much more of his paper now.

This paper from the IMF showed there was a real positive correlation between IMO scores and future knowledge production, as well providing this fantastic quote (emphasis mine):

The conditional probability that an IMO gold medalist will become a Fields medalist is fifty times larger than the corresponding probability for a PhD graduate from a top 10 mathematics program.

Using a regression discontinuity analysis they provide evidence that getting a gold over a silver didn’t directly cause future output improvements (i.e. it was evidence against the signaling hypothesis), but that scoring higher generally did. And finally, they also broke down future career paths into academia, tech, finance, and other, which I will also do in section four.

This paper tracked the outcomes of Chinese gold medallists but mostly laments the lack of their output post-IMO success.

Section Two: Is my data trustworthy?

Feel free to skip this part if you aren’t skeptical by nature.

I gathered undergraduate, PhD, current workplace, and job title data for gold medallists from 1997-2017. I didn’t look for post-2017 medallists because even some of the 2017 cohort are still undergraduate students and I cared more about outcomes a little further along in their careers. I didn’t look for pre-1997 medallists because, frankly, curating this dataset already took a very long time.

The dataset consists of 909 gold medals: 730 unique gold medallists from 59 different countries.

I need to make a few comments and observations about the dataset.

Search tools

This was basically an exercise in ‘Googling stuff good.’

Obviously LinkedIn was a vital resource for this search. But to my dismay if you have a gold medal it seems like you don’t need LinkedIn as much as the rest of us

Results from the International Mathematics Competition for (mostly European) University Students and the Putnam Competition for US students were helpful in finding where they went for their undergraduate studies. Once I had their undergraduate location, I could narrow the search a little more.

arxiv.org was another helpful place to find names with references to where they were employed if they had published any math papers.

I tried to get ChatGPT/perplexity.ai to search for me and provide citations. I had occasional success, but enough hallucinations that I stopped pretty quickly.

Data biases

My dataset is English-language biased because I could most easily search for candidates in English.

I tried using Google Translate and Google Search/Baidu/Yandex to find other languages but it was sufficiently clunky that I didn’t have any luck doing this.

I tried using freelancing services to offload some of this task, but a couple I used weren’t trustworthy enough for me to delegate this to.

Japan, Russia, and South Korea were tricky to track. I think this is because a lot of them stayed in their home countries and their web footprint is non-English.

Vietnam was tricky to track as well. I think this is because a lot of them end up using English names that aren’t easily guessable and also, as we’ll see later, the Vietnamese participants attended a wider variety of undergraduate institutions than others.

China was tricky to track due to both a non-English web footprint and, for those who moved West, an adoption of English names.

There’s almost no information about competitors from North Korea online. From tidbits on Ri Jong-yol’s Wikipedia page I am a bit concerned they were recruited into North Korea’s elite hacking unit and so will stop writing about them from here on out.

If have made it this far and want to help me search the Russian, Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, or South Korean-speaking internets to fill out my datasets, I would be eternally grateful and willing to pay. The biggest issue with this entire post is the bias on missing data. I suspect it won’t change too many of the larger conclusions but I am likely missing a story or two in the data.

Sanity checks

It’s always good to sanity check your data when you’re using it for real world analysis. I ran the dataset through ChatGPT to check for typos and display some overall stats here that confirm things look ok.

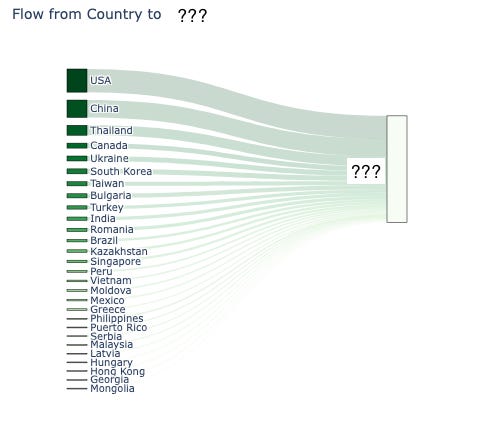

1. Where are they from?

My dataset was initially built from the IMO website participant data, so our gold medal counts match.

By total gold medal count, China is the clear leader, followed by the pack of USA, Russia, and South Korea. Over 20 years China has 105 out of a possible 120 gold medals which means nearly all their students achieved gold. This is so successful that it’s common knowledge that it is harder to make the China IMO team than to get a gold medal in the IMO itself.

2. How much data is missing?

For some medallists I couldn’t find anything online. For most I could find something. Overall I found information for 91% of the medallists in my dataset. Unfortunately they were quite biased per country in large part due to the sources and language I was searching in. Thankfully I wasn’t missing more than 26% of the data for any country (barring North Korea).

Country Percent of rows missing Total rows missing

China 10 21

North Korea 100 19

South Korea 18 16

Russia 12 14

Vietnam 26 13

Japan 11 7

Ukraine 6 5

...

Romania 0 0

Thailand 0 0

United Kingdom 0 0

France 0 0

Australia 0 03. Sanity checking academic job titles

Academic job titles follow a relatively standard progression in many cases:

Student → PhD → Postdoc → Assistant Professor → Associate Professor → Professor

There are variants on this, including titles like Instructor, Lecturer, and Researcher but the majority of titles are standardized. I plotted the frequency of these titles by cohort to check that they roughly correspond to time in academia.

At a glance this looks appropriate:

The more recent cohorts are still doing their PhDs and some are in fact still undergraduate students.

The larger numbers in academia (in particular doing PhDs) from recent cohorts relative to earlier cohorts is due to many students leaving academia after completing their PhDs. I’ll say more about this later.

The middle cohorts are doing their post-docs and are pre-tenure professors

The further back your gold medal, the older you are, and the more likely you are to have reached the top of your field as a Professor. Looking at the earliest gold medallists, about 15% of the cohort ends up a full Professor and another 15% ends up a tenured Associate Professor. I’ll dig more into this in section four.

Why are there so few people from the 2007 cohort who ended up in academia? I suspect it’s just random noise.

Initial Conclusions

My dataset is novel and passes the various sniff tests I threw at it. And no-one else has written in depth about the outcomes of the recent IMO gold medallists.

I’m excited to dig into this more in the upcoming posts. There I’ll look into where they went and what they did after winning this competition.

Please subscribe to be updated when I do!

Where have the International Math Olympiad Gold Medallists Ended Up? Part Two of Three

In part one of this series, I was amused by some crazy outcomes of IMO gold medallists, verified that the dataset I had built that tracked their subsequent steps looked appropriate, and confirmed that no-one had done as new and large scale an analysis.

Some sneak peeks for the next post.

Try and guess in the poll below which undergraduate institution gets the most IMO gold medallists

Try and guess which country sends their kids to these universities to undergrad.

Did you mean to link to that IIT professor's main page? In searching for his relevant post, I stumbled upon other posts containing many angry and even violent thoughts.