Where have the International Math Olympiad Gold Medallists Ended Up? Part Two of Three

The echoes of colonialism, one university to rule them all, and a grand unified theory of mathematics

In part one of this series, I was amused by some crazy outcomes of IMO gold medallists, verified that the dataset I had built that tracked their subsequent steps looked appropriate, and confirmed that no-one had done as new and large scale an analysis.

Here, I look into what the data actually tells me.

Table of Contents

Section Three: Undergraduate Institutions

Where do they go?

You are 18 years old and have just won a gold medal at the IMO. You’re currently on top of the world. National newspapers interview you. All doors are open to you. All paths available. Which do you take? Most importantly, where do you go to university?

The short answer is: you will go to MIT.

Ok, that’s not quite true. MIT is by far the most popular university while being one of the smallest universities on this list. So the density of gold medallists is even higher than the above chart suggests. But students don’t just go to MIT.

I would have initially guessed these gilded students would end up spread in a power-law like fashion across the top N ranked universities globally. But as we go down the list, from the above chart we quickly see elite national universities that don’t have the same global presence. And frequently these were the destinations for the top students in their country.

When they weren’t, MIT was standing ready with its arms wide open.

But more specifically where?

I have the data to ask who goes where, specifically? Here are a couple of Sankey diagrams showing the flows from country to country, and from country to university.

Let me briefly explain these Sankey diagrams. In the first one, on the left side, we have the countries that students represented during the IMO. On the right side we have the countries they ended up in for their undergrad studies. And the thickness of the line connecting country A on the left to country B on the right is proportional to how many students went from representing country A to going to undergrad in country B.

In the second diagram the left hand side is the same but the right now lists specific universities.

In both cases for clarity’s sake, I’ve only included connections when at least 4 medallists took that path. This shows the main stories. However in chart 1 in the appendix at the bottom of this post, I’ve displayed this same diagram with all connections for those interested. It’s much messier but I found it interesting so left it in.

There are lots of stories to unpack here!

The Americans go predominantly to MIT or Harvard. I was surprised other top US universities (Stanford, Yale, Princeton etc) were almost non-existent, but maybe the focus on well roundedness at other universities works against their recruitment of these medallists?

While a majority of Chinese medallists stay in China, a large minority go to MIT, and none go to Harvard (burn). In fact I noticed while curating the dataset that a lot of students start at Peking University and then transfer out to MIT after two years. This is corroborated from reading the bio of Xianyi Zeng. It seems like all IMO gold medallists get automatic entry to Peking but plenty of them transfer out after a couple of years.

The Russians split their loyalties between a few different universities all inside Russia. Moscow State University (MSU), Moscow Institute for Physics and Technology (MIPT), Saint Petersburg State University (SPbSU) and the Higher School of Economics (HSE).

Most countries do a good job keeping most of their top students for undergrad in one university. Iran, Korea, Japan, Hungary, UK, and Taiwan keep almost all of their students at their top university. Reasons probably include: international fees, language barriers, the desire to socialize with people who are culturally similar to you, local scholarship awards, agglomeration effects, and you’re just young at 18 and don’t want to go too far from home yet.

Almost no country outside of the USA see any inflows from other countries. This is probably due to some language barriers and the top globally recognized mathematical institutions being in the USA.

Actually, almost no other university sees inflows from other countries, except MIT.

MIT

Why is MIT such a large attractor of international talent? If we zoom into the MIT portion of the diagram and drop the thresholding, we see that MIT takes talent from all over the world.

There’s no real pattern here from what I can tell. When I look at where people go for PhDs the flow of medallists is a little more spread across institutions but that’s for section four.

There’s enough chatter on the internet about MIT’s medal-focussed international applicant admissions process that MIT has to deny they only admit those with Olympiad distinctions but they still encourage it.

And my understanding is MIT’s application process has much shorter essay questions than others which probably favors non-native English speakers relative to longer essays.

Vietnam

While most countries that have a strong showing at the IMOs tend to send their gold medallists to the top universities in either their own country or in the US, Vietnam stands out as different.

Ecole Polytechnique in France is actually the main destination for Vietnamese medallists. For most other countries it’s MIT or a geographically close university like, in this case, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST). This is most likely due to the historical occupation of Vietnam by France, the subsequent reduction of language barriers, and the leftover cultural influences of the French.

A Vietnamese IMO medallist friend told me his approach to applying for university was to rank US colleges by the amount of financial aid they could provide. He ended up going to a decent university, and has done well since then, but it wasn’t one that appears on these lists.

There’s a story here of a missed opportunity for him and others like him to be fully funded at an MIT or Harvard. The IMF paper I mentioned in part one also noted an underutilization of talent from lower GDP countries.

Section Four: What’s next for them?

To PhD or not to PhD?

You are a 22 year old student. You’ve just aced MIT’s undergraduate course with a 5.0 GPA. What do you do next?

A PhD, probably. But it actually depends on what year you graduate.

73% of gold winners in my dataset for whom I have information end up doing a PhD. But that’s been declining over the past 20 years.

My guess is that as tech and finance jobs have gotten more numerous and lucrative, the alternative has become more and more appealing.

Academia, tech, or finance?

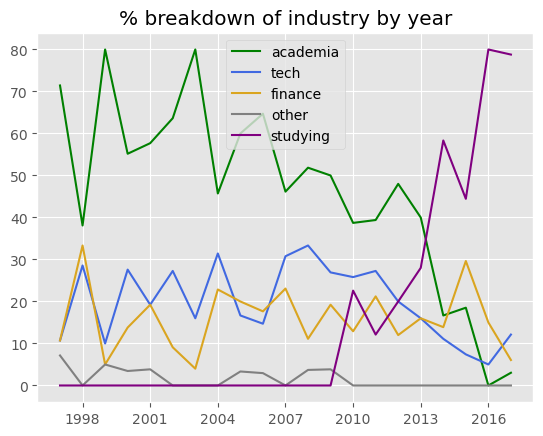

Below I plotted the % of gold medallists going into different industries based on when they got their final gold medal.

The groups are mostly self explanatory. Those doing Phds/undergrads were put into the “studying” group, and those at post-doc or higher were put in “academia”.

Using data from pre-2010 cohorts (who are all done with their PhDs), we can see:

Academia is where about 60% of students end up. Note that I didn’t classify their PhDs by subject like Yuret did in his paper but most of these academics are in math, CS or economics. A few of the Japanese and South Korean academics ended up in materials science and physics.

Tech and finance account for 15-30% each. Tech is ahead most years but finance overtakes them in more recent cohorts.

As you might imagine this accounts for pretty much all the outcomes of these kids. There are a few outlier jobs like Buddhist monk and freelancers that I classified into “other”.

And of course the more recent your gold medal, the more likely you are to be studying as an undergraduate or PhD student still.

Academia

We already know that a plurality went to MIT for undergrad. Did that continue into grad school?

Yes.

The other US universities catch up a huge amount while the Chinese universities drop off a lot. Note here is one major place my dataset bias mentioned in part one might cause an incorrect ranking.

Another way of showing a little more information is our favorite thresholded Sankey diagram.

The first shows country of undergrad → country of PhD, showing only links when there are 2+ people taking that path. Chart 2 in the appendix shows this unthresholded.

The second shows country of birth → PhD institution showing only links where 3+ people too that path. Chart 3 in the appendix shows this unthresholded.

Another set of plots that tell a lot of stories.

USA’s PhD dominance amongst gold medal winners is absolutely massive.

MIT’s dominance has waned but it remains the top place for global students. I imagine there simply aren’t enough PhD positions available at MIT each year so the students are forced to go to no-name schools like Stanford and Berkeley.

China, Iran, and South Korea lose a lot of their students to PhDs at the big five US universities even though they keep most of them for undergrad. Those are MIT, Harvard, Stanford, Princeton and Berkeley. “Happy Monkeys Swing Past Bananas” is a fun acronym to remember them.

In fact Russia and Japan are the only big countries that are able to hold on to their undergraduates.

The Langlands Program

While searching for these 700+ students, I frequently came across the academics working on something called the “Langlands program”. In case it’s not obvious yet, I am vaguely interested in math, but I had never heard of this before even though, per Wikipedia, it is “widely seen as the single biggest project in modern mathematical research”.

I read the four answers and provide here the one I found most illuminating.

Imagine you have a bunch of toys, like blocks and balls, and you're trying to find a special way to match them together. The Langlands program is like a magical game where very smart people try to figure out how different toys can be connected in a special way that makes sense, even if they look very different at first.

Quanta Magazine provides a slightly longer intro to it if you are left unsatisfied.

If you’re a gold winning IMO medallist now working at a top university, with your 50x higher likelihood of winning a Fields medal, you probably want to aim at the biggest baddest problems in math. This seems to be that.

It also turns out that some medallists don’t want to unify number theory and geometry. Some just want to buy low, sell high, and watch number go up. Some don’t get the job they want in academia and turn to the dark side next best option for them: finance.

Finance

Job titles in finance are famously not descriptive. Pretty much working everyone at quant trading firms and hedge funds call themselves a “quantitative researcher”. These days most of the top mathematicians in finance are at these firms.

Citadel, Jane Street, Two Sigma, Jump Trading, and HRT are the top five employers from my dataset and they’re all primarily in the business of buying low and selling high. They do this pretty well by all accounts.

Below are the firms with more than 2 gold medallists.

If you’re an IMO gold medallist, you are at least a little bit competitive with other people. One place you can directly and legibly compete against other smart quantitative people is in the world of quantitative trading.

The side effect of winning the finance competition is that you’re paid well. A lot of people I know in quant finance love most the feeling of winning against the markets and against other smart people. And they live relatively frugal lives despite their considerable remuneration.

The quant growth in recent years

Here again is the chart showing the breakdown of industry by year:

Note here that getting a gold in 2013 means you will finish undergrad around 2017.

There’s an obvious pipeline of PhDs → academia because that’s a requirement of the job. But of course some PhDs go into finance and tech. In fact just over half of the gold medallists working in finance have PhDs.

Between 2010 and 2016, we see that the “academia” group declines as the “studying” group increases. Similarly the “tech” group declines as the “studying” group increases. But we don’t really see a decline in the “finance” group.

Citadel, Jane Street, Jump Trading all had double digit headcount growths in recent years, spurred on by market volatility since the Volmageddon in 2018 and then COVID. This is when the tech line declines while the finance line does not. More undergrads are leaving the PhD pipeline for quant finance than before.

At first I thought it could be explained by a story of more people simply going into quant finance. This would mean that in the future, the yellow line representing quant finance between 2014-2018 would rise as newly minted PhDs find themselves in quant finance. This was the story I kind of wanted to see from the data.

But it seems just as possible that the same people who would have done a PhD then gone into quant finance are instead just going straight into quant finance.

Why is that the case? I’ll have a bit more to say about this in the next post.

I don’t know yet where these new medallists into quant finance are coming from. Are they being poached from tech or lured from academia? Is Citadel just becoming really good at converting Buddhist monks and North Korean hackers into quants? Did one person at MIT drop the ball on this?

Tech

The final large sink for IMO gold medallists are the tech companies. Actually, when you look at the data for half a second you realize that it’s almost entirely Google. In this dataset, Google is the MIT of tech companies.

Below are the firms with more than 2 gold medallists.

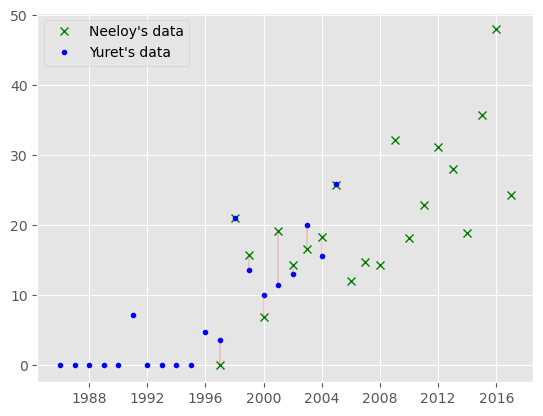

Yuret finds a similar preponderance of medallist-Googlers:

Google stands out with the highest concentration of medalists, employing a total of 91 medalists […] Microsoft, Meta, Citadel and D.E. Shaw & Co employ 27, 17, 15, and 13 medalists

But while he found that Microsoft had the second most, I found Microsoft trailing amongst more recent medallists in my dataset. Instead Citadel was in second place outside of academia.

This is either because my dataset is more recent, or because Microsoft has a disproportionate number of silver and bronze medallists. Luckily Yuret provided me access to his dataset so I confirmed that it was because Microsoft has very few gold medallists and a lot of silver/bronze medallists.

Google and Meta are 20-50 times bigger than Citadel and Jane Street, so the proportion of IMO medallists at these quant firms is much higher than at Google.

As someone who has worked in both tech and in finance this roughly matched my experience. Tech companies definitely had some of the smartest people around, but the quant finance companies, which were much smaller, had a higher bar for admission.

Where are they literally right now?

Combining everything above, here’s the definitive plot of where the IMO gold medallists are right now. This includes people doing their PhDs, which skews the results to MIT’s favor.

If we remove the current PhDs and just look for medallists in post-student life we see Google overtaking MIT as the top place for IMO gold medallists.

The modal IMO gold medallist went to MIT for undergrad. They went to MIT for their PhD as well. And they’ve ended up at Google.

I have some other questions that I can answer by splitting my data along the other dimensions I have.

Do professional outcomes vary by country? The IMF paper implies that the productivity of researchers varies by country, but I’d be curious if one country is disproportionately sending their kids to finance or tech. Specifically, are medallists from lower GDP countries ending up more in finance/tech?

Do professional outcomes vary by undergrad institution? There was a joke that we could never get Stanford students to move to Chicago for quant finance jobs. Instead they all stayed on the West Coast for the weather and therefore ended up in tech. Are there undergrad (or geographical) biases in professional outcomes given that finance skews east coast, tech skews west coast, and academia is all over the place?

But this post is already very long. If there’s interest I’ll dig more into these and other questions in a separate post (Part Four of Three?). Please leave a comment if you’re curious.

Conclusions so far

MIT is far and away the leading place for gold medallists for undergrad. It’s not even close.

Harvard, Peking, or Cambridge should fund a Vietnamese IMO medallist scholarship to bump up their numbers to catch up to MIT. Peking University, at the very least, should figure out how to stop their brain drain to MIT.

70% of medallists go on to do PhDs, but that’s declining quite fast.

The US is by far the most common place to end up doing a PhD. The big five universities of Happy Monkeys Swing Past Bananas are where the majority of PhD gold medallists end up.

More than half end up in academia, but I forecast that to decline with the growth of quant finance. A lot of academics are working on the Langlands program.

Google is the MIT of tech companies - nearly all tech gold medallists are at Google.

Sneak peek at the final post

Appendix of unthresholded Sankey diagrams

Chart 1 - here’s the full flow of gold medallists from birth country to undergraduate institution.

Chart 2 - here’s the full flow from country of undergrad to country of PhD. The US’s dominance grows.

Chart 3 - here’s the full flow from country represented to PhD institution.